Fermi National Accelerator Lab

My 2 summers working as an automation research intern at FNAL. I completed my MS program as a GEM fellow, and my industry sponsor was FNAL.

Intro

As part of the GEM fellowship program, students are matched with employers which in return for tuition sponsorship of the student’s graduate program expect students to complete summer internships until graduation. I matched to Fermilab and as part of my fellowship program got the opportunity to complete two summer internships at Fermi. Fermi is America’s premier particle physics research lab which for a while housed the world’s largest, most powerful particle accelerator. While that title goes to CERN now, Fermi is still at the forefront of particle physics research, now focusing on dark matter, dark energy, and stress-testing the standard model of physics.

I am by no means anything close to a particle physicist, but as an early career engineer I never back away from an opportunity to learn. Fermi drew me because the level of engineering required to execute a lot of their experiments is incredible. During my time at Fermi I was exposed to two central focuses of the lab: radiofrequency cavity assembly, and the mu2e experiment. I was incredibly lucky to have these two experiences because they exposed me to areas at opposite ends of the science stack of Fermi.

Superconductive Radio-frequency Cavities (SRF)

In my first summer I was an intern under the Applied Physics and Superconducting Technology Division APS-TD which focuses on the research and development of superconductive magnets and cavities for general purpose applications. Work from this division has impact across the lab and as well as the broader particle physics community.

Radio-frequency (RF) cavities are essential for high-energy physics because they are source of acceleration for particles passing through the accelerator complex. I was always into Hot Wheels sets when younger, so that is the best analogy I have for understanding the role of cavities in particle accelerators: particles can be thought of as the little cars that are moving through the track, and the RF cavities are the stations which propel the cars forward. You can imagine that if you make the track circular the cars will move faster and faster with every lap (neglecting friction effects), and that is exactly the reason why particle accelerators are circular.

The strength of the electic field produced inside a cavity is ultimately what dictates how strongly particles accelerate through them, and higher the electric field the more energy that is required to opperate the accelerator. The limitation here is efficiency–power dissipations at strong electric fields can jeopardize the stability of the accelarator and can also simply make the operation infeasible due to the large power requirements. The reason all this is important context is that superconductive RF cavities are orders of magnitude more efficient that traditional cavities, making them essential for the new generation of particle accelerators. With SRF cavities, accelerators have been able to accelerate particle beams to new horizons, which has led to incredible new findings including the Higgs boson.

My project

SRF cavities are chained together into “strings”, but this process needs to happen with ultimate precision and the utmost care for contamination because contaminants can very easily compromise the cavity’s performance and can lead to beam instability. This process is currently done by hand, and due to rising demand for SRF cavity strings, Fermi along with other institutions is interested in exploring ways to automate this process. My summer project sought to do requirements gathering for potential automation cells, and I came up with a high-level idea of using a stewart platform for cavity alignment. My main deliverables of this summer were a presentation outlining the engineering requirements for an automation system given all the input I received from lab scientists and engineers, and a research poster which I presented at a lab-wide symposium.

Mu2e experiment

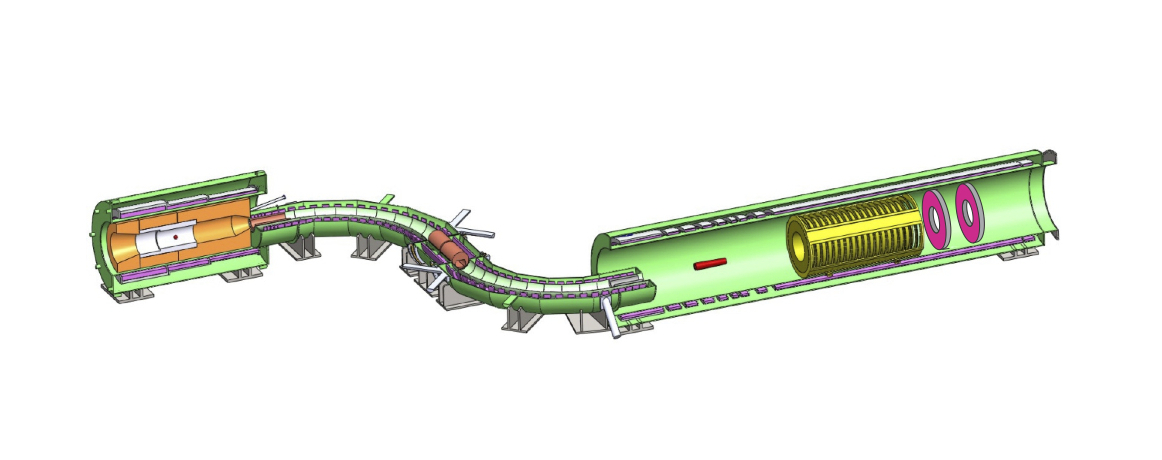

My second summer I was an intern under the Accelerator Directorate AD working on target systems. Several of the flagships experiments going on at the lab at the moment fire a beam of particles into a static target. This is an engineer’s simplification, so please take it with a grain of salt.

Mu2e is an experiment looking to study the decay of muons into electrons to determine if it conflicts with the predictions of the standard model. If you are interested in reading more into the physics of this experiment, I recommend checking this write-up on Charged Lepton Flavor Violation CLFV. Automation is relevant in mu2e and other experiments involving targets because many times when a high-energy particle beam is fired at a target, ionizing radiation is produced creating a hazard for scientists and engineers involved in the experiment. For this reason, having automation systems that can do handling of the targets and other compenents of the experiment is highly valuable.

My project

The remote handling machines of mu2e serve the primary purpose of replacing the static target of the experiment. This target exchange needs to happen roughly once a year, therefore precision is of utmost importance. The first objective of my summer project was to design fixtures to make the installation of the different end effectors of the robot arm easier. The second objective of my summer project was to write firmware for the cart-door system. This system includes a 2-ton radiation-shielding door which controls access to the experiment room during target exchanges, and it also includes transport carts for moving the remote handling machines into and out of the experiment room. This second project was especially tricky because all of the motors and motor drives offered different communication protocols (Modbus RTU, ASCII, and TCP), and the central PLC we needed to control this system had its own communication requirements. Ultimately, I was able to identify a suitable communication protocol for each component, and I integrated the drives into a benchtop system which I created PLC programs for to demo its functionality.